There’s nothing like the impending arrival of 15 million war vets to help jumpstart a devastated housing market. After a 90 percent drop in production of new homes at the beginning of the Great Depression, homeownership hit a century low of 43.6 percent in 1940—four points lower, even, than when the Depression began. Then, to make matters worse, in April 1942, the War Production Board issued Order L-41, which brought non-war-related housing construction to a grinding halt. When the order was lifted a month after the war ended, Time magazine declared, “Builders got the go-ahead for their biggest boom yet, almost entirely free of government control.”

It was true. By the time Order L-41 was lifted, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had already signed into law one of the most powerful pieces of postwar legislation: the G.I. Bill of Rights. Formally known as the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, the bill intended to avoid the economic strife American vets experienced after World War I, when most received just $60 and a train ticket home.

The G.I. Bill almost single-handedly built the American middle class by addressing core social needs—unemployment, education, and health care—and, importantly, it did so through government-backed, low-interest, fixed-rate mortgages with zero or low down payments and up to 30-year terms. In effect, the G.I. Bill put homes within reach of all but the poorest American vets.

By 1952, 2.4 million veterans had received government-backed loans. A new class of postwar homeowners was born—and they looked awfully alike.

A New Kind of Suburb

Homeownership was positioned as an emotional balm, of sorts, against the turbulent and not-so-distant past. In 1942, President Roosevelt himself tied homeownership to a spirit of strength and optimism, saying, “A nation of homeowners, of people who won a real share in their own land, is unconquerable.”

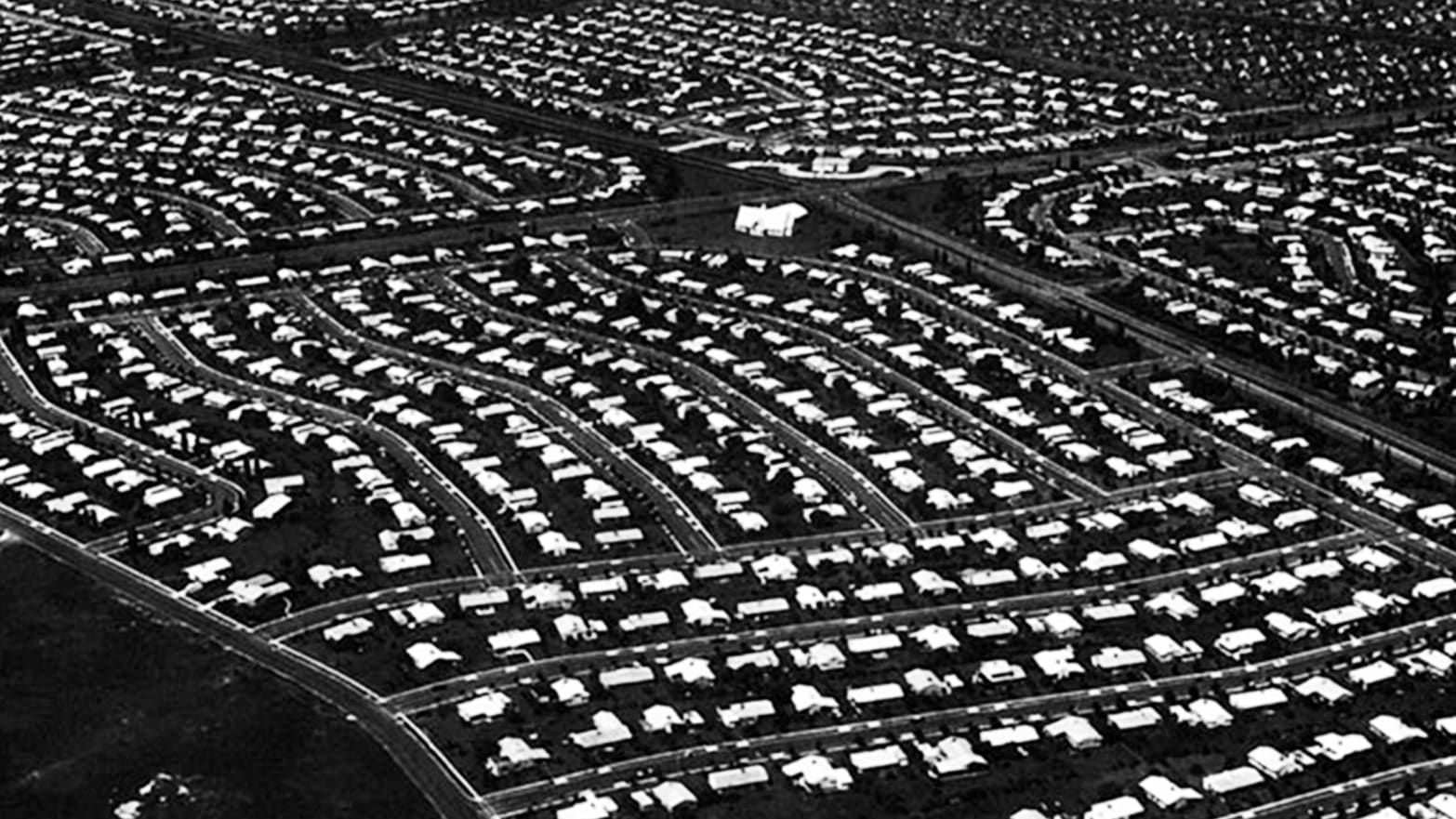

Those homeowners, however, were leaving dense urban centers in droves. The terms of the government-backed loans favored new construction, and cheap land outside cities soon grew into suburbs filled with rows of modest 800-square-foot Cape Cods, providing just enough room for a G.I., his wife, and their proverbial 2.5 kids. The homes “represented the American Dream reduced to its basic minimum,” wrote Barbara Kelly, author of Expanding the American Dream, in The New York Times. Suburbs had existed before, but not at this scale—and not within such easy reach.

The economics just made sense. In 1946, a newly constructed six-room home in the suburbs came with a price tag of around $5,150. Thanks to government-backed mortgages, the typical down payment was roughly $550 with a monthly mortgage payment of $29 and change, paid over a period of 25 years. Meanwhile, back in New York City, with its creeping urban blight and festering slums, a similarly sized apartment ran $50 per month. Who wouldn’t want to leave?

By 1950, suburban growth was 10 times that of urban cities and, for the first time, more than half—55 percent to be exact—of Americans owned their own home. That represented an astonishing 11.4 percent growth from the all-time low, just a decade before. And thanks to redlining practices, which kept racial and religious minorities from qualifying for mortgages as part of U.S. housing policy, and overtly racist covenants, which kept them out as part of real-estate deeds, that growth was almost completely white. As a typical covenant of the time—this one from a neighborhood in Seattle—put it: “That no part of said property hereby conveyed shall ever be used or occupied by the Hebrew, Ethiopian, Malay, or any Asiatic race.” By the early 50s, only 2 percent of homes built with government-backed mortgages since World War II were occupied by African Americans or other minorities.

Levittown U.S.A.

A shining example of what made the idea of suburbia so powerful sits 25 miles east of Manhattan in Levittown, Long Island.

Back in 1947, the real estate development company Levitt & Sons brought mass production to suburban housing, proclaiming itself “the General Motors of the housing industry.” On July 1 of that year, company president William Levitt broke ground on a seven square mile tract of potato fields—and transformed it into a collection of more than 17,000 modest standalone homes. Each one was a more or less identical: 750 square feet with two bedrooms and an unfinished attic set on a 60-foot-by-100-foot plot of land, with a car port and a tree out front. At Levittown’s peak, a home was built every 16 minutes.

Levitt homes initially cost around $6,990. Vets slept outside Levitt’s office for days to capitalize on a deal he announced in 1948—keys to a Levitt home for a $90 down payment and $58 per month for the first 350 people to show up on a Monday in March. The police had to be called in to help manage the crowds.

What Levitt built, in essence, was the template for a new kind of American community. Around the time the last home in Levittown was built in 1951, 80 percent of its male residents were commuting to work in Manhattan. And like so many postwar suburbs, it was 100-percent white by covenant—never mind that that U.S. Supreme Court had found restrictive covenants a violation of the 14th amendment a couple years prior.

In August 1957, in another Levittown, 100 or so miles away in Pennsylvania, William and Daisy Myers, an African-American couple, and their children moved into 43 Deepgreen Lane. Months of grotesque racial conflict ensued—rocks thrown through picture windows, angry mobs, hundreds strong, burning crosses on the lawns of anyone who befriended the inhabitants of the one African-American home among more than 17,000. (If it all sounds familiar, a recent movie drew from this story.) The Myers remained for four years, despite continued threats, until work took them elsewhere. The racist history of Levittowns across the U.S. lasted much longer. To this day, Levittown, New York is still less than 1% African American.

All the while, Levitt positioned himself as not a racist, saying, “As a Jew, I have no room in my mind or heart for racial prejudice … We can solve a housing problem, or we can try to solve a racial problem, but we cannot combine the two.” It wasn’t the first—and it wouldn’t be the last—time housing would be the foil for America’s deeply dysfunctional relationship with race.

Meanwhile, Back in the City

As the suburbs thrived, urban areas crumbled. By the late ’40s, white flight left the image of urban blight and slums increasingly black, brown, immigrant, and poor. (That said, African-American suburbia did exist—the African-American suburban population grew by almost a million in the postwar era).

Enter the Housing Act of 1949. Its primary goal, per President Truman, was “a decent home and suitable living environment for every American family”—“every” being code for even those residing in the inner city. The act authorized funds to assist in slum clearance, with varying degrees of acceptance by the slums’ inhabitants. “That slum clearance will result in ‘Negro clearance’ is already a strong and growing Negro feeling in the larger cities,” wrote George Nesbitt, a pro-public housing civil rights lawyer who later went to work as deputy assistant for the secretary of Housing and Urban Development in the Kennedy administration.

For its part, in 1952, the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB), now known as the National Association of REALTORS® (NAR), launched a campaign called “Build American Better,” a “three-fold attack on urban blight and slums.” It strove to enforce housing codes, encourage new construction, and improve parks, streets, schools, and sewers. It was an ambitious plan that stressed renovation and rehabilitation over slum clearance and public housing, with a goal of rehabilitating 10 million buildings. Then Realtor® association president Joseph Lund called the approach slum “curance,” as opposed to clearance. It was a stance the federal government would later adopt as part of the Housing Act of 1954.

Here Come the ’60s

By the end of the 1950s, the average household income was $6,691, 57.9 percent higher than it was in 1950 and 178 percent higher than it was in the middle of the Depression. Home ownership rose past 60 percent. U.S. housing policy powered this new era of homeownership—and the future economic windfall that came with it as equity grew and homes appreciated. Indeed, an original Levitt “Rancher,” bought for $8,000 in 1950, sold for $297,500 in 2015, an unbelievable 3,600 percent return on investment. Then, as it is now, homeownership was, in the words of real estate expert David Bach, “an escalator to wealth.”

But not everyone was on the way up.

Virtually an entire generation of African Americans missed out on their 750-square-foot piece of the American dream. Even as laws changed, the Supreme Court stepped in to put the kibosh on racial covenants, and the Federal Housing Authority stopped endorsing redlining as official policy, the damage had been done. Postwar suburbia—a symbol of America’s new middle class, optimism, and cookie-cutter conformity—had segregation coursing through its veins. It would only take a short while longer to see the toxic effect that would have across America.

REALTOR® is a federally registered collective membership mark which identifies a real estate professional who is member of the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF REALTORS® and subscribes to its strict Code of Ethics